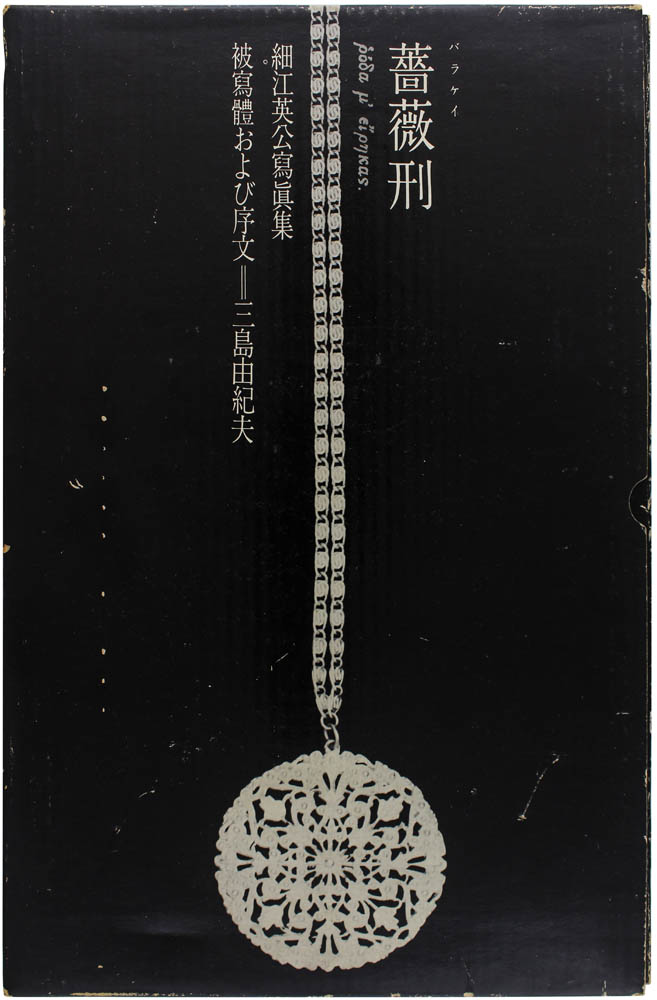

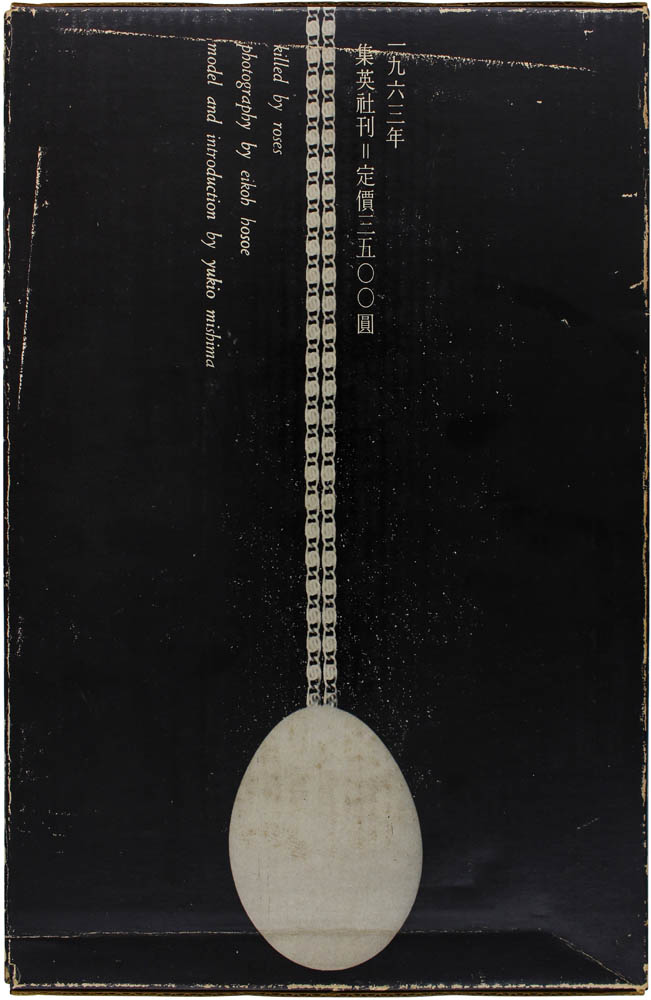

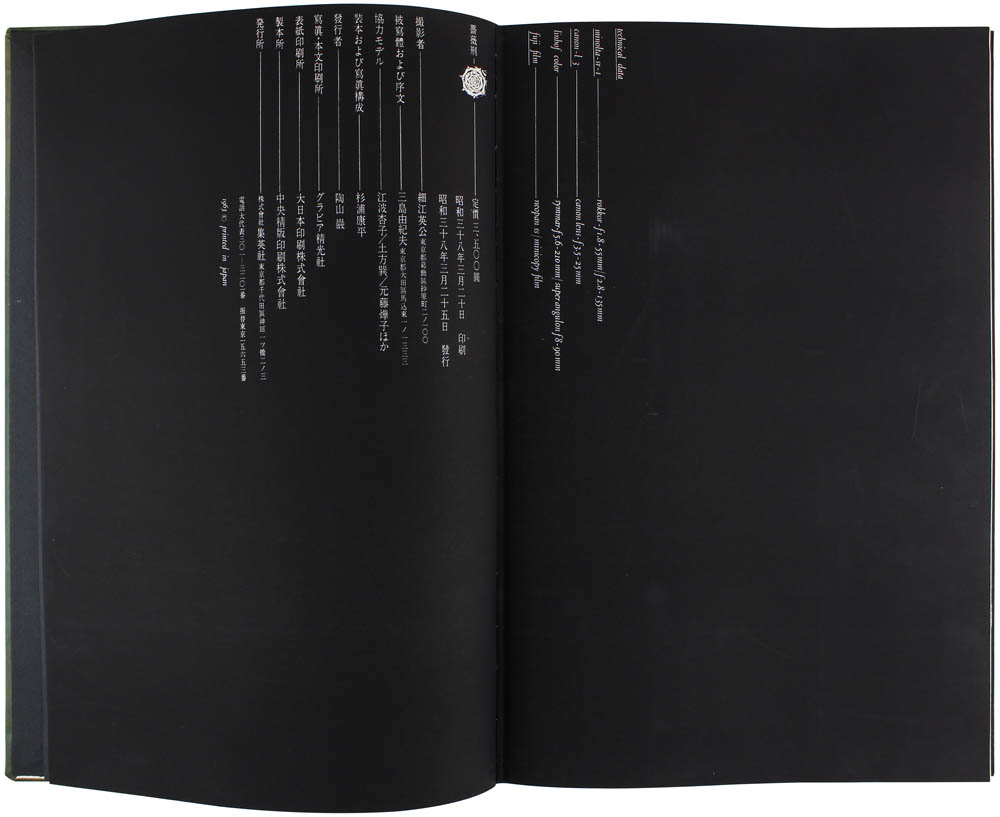

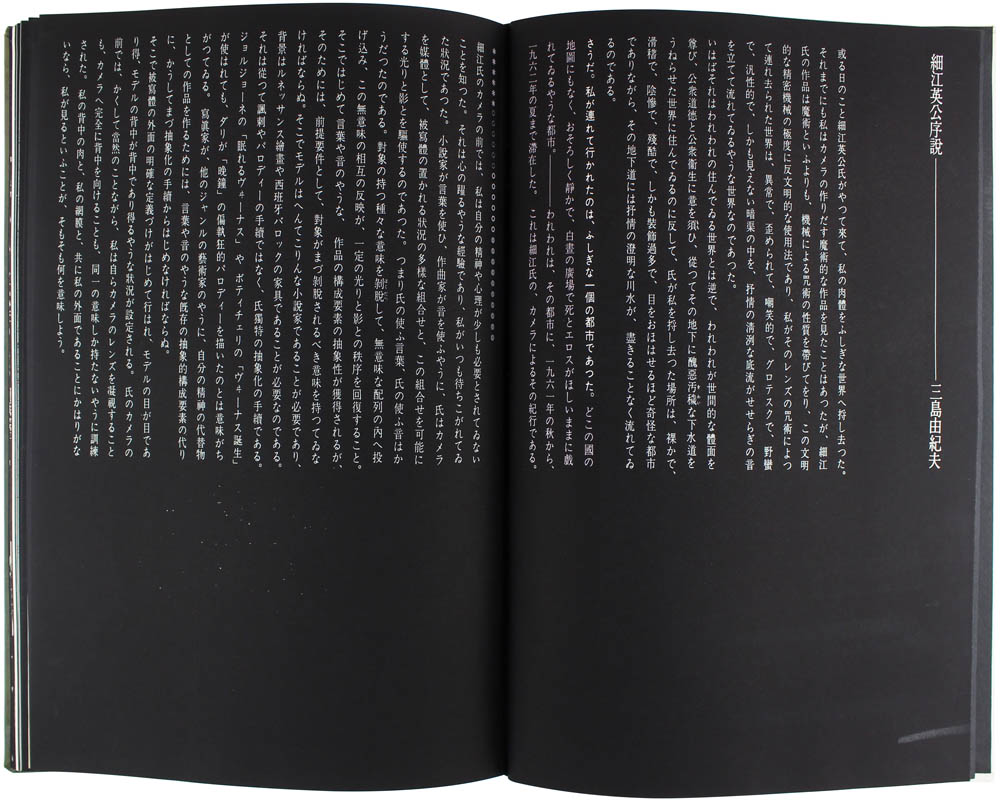

EKIOH HOSOE BARAKEI SERIES

“All I want to photograph is the life and death of yourself, through you”

- Photographer Ekioh Hosoe to Author Yukio Mishima

When Ekioh Hosoe made this pronouncement to the subject of his Barakei series of images, he did not know how soon his words and photographs would take on such haunting layers of meaning.

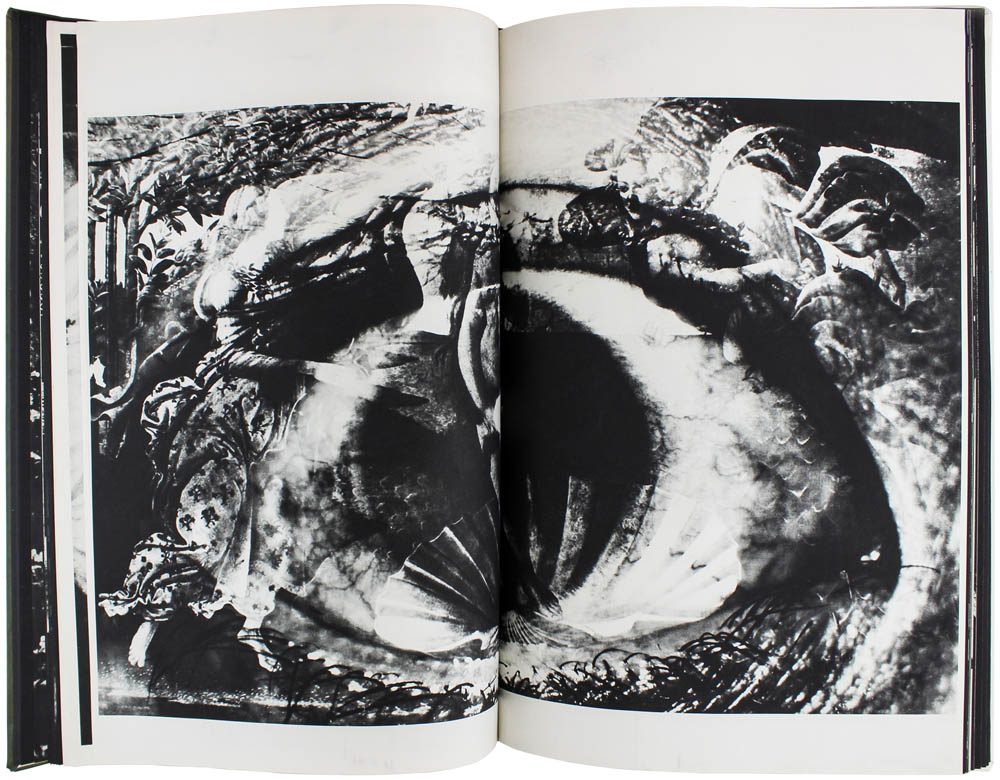

Hosoe’s works have always been laced with the supernatural. His childhood provided fertile fields from which to draw the mingling of the hominine and the spiritual. At the age of seven he served at the Shirahige Shrine in Tokyo at the behest of his father, a Buddhist Monk. And like most Japanese children, he was fed tales of yōkai, supernatural spirits, demons and monsters, mischievous, mythical creatures who could wreak malice on humans at one end of the scale, or sprinkle good fortune at the other.

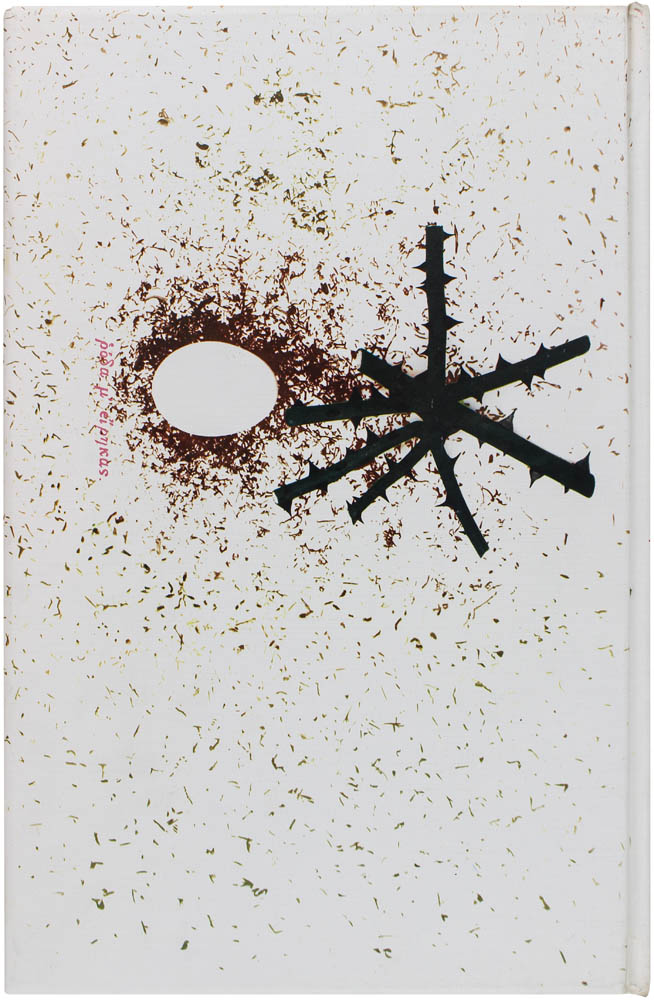

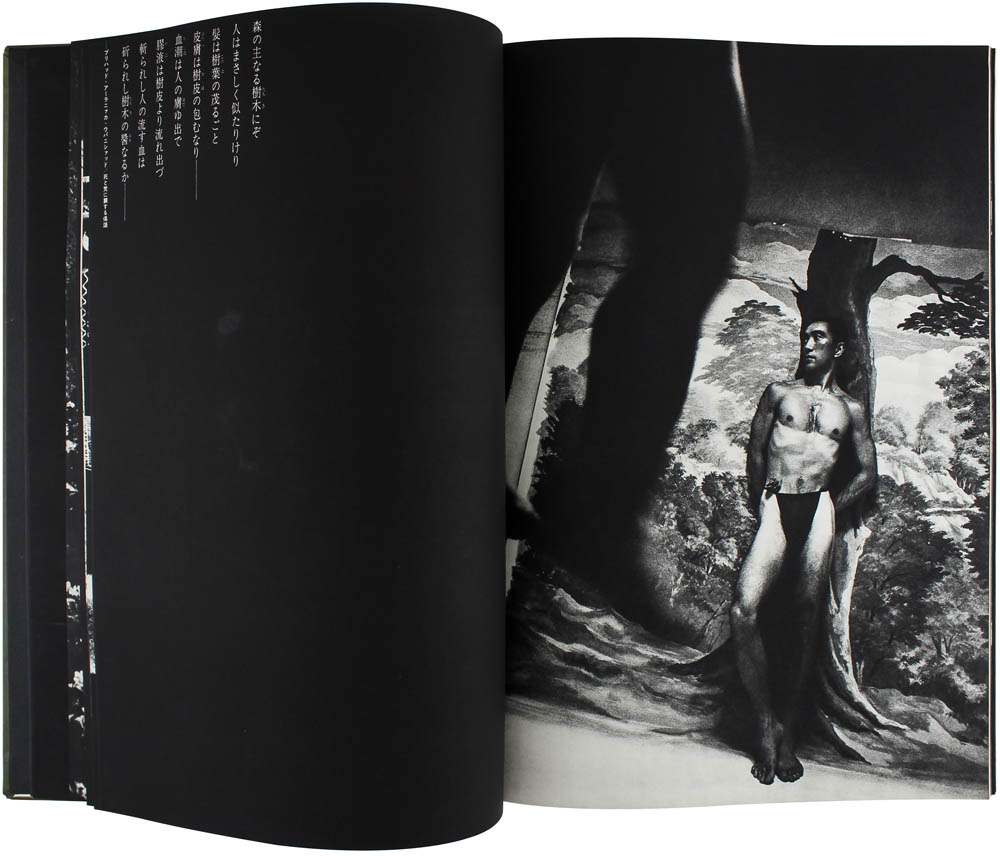

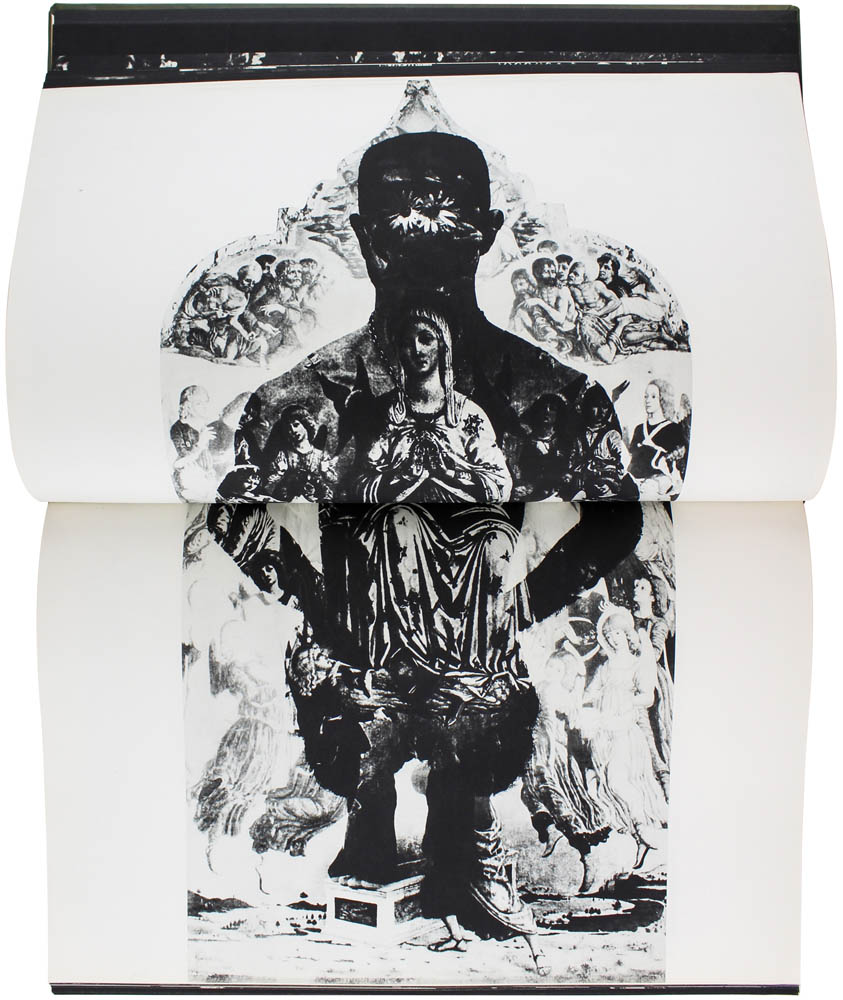

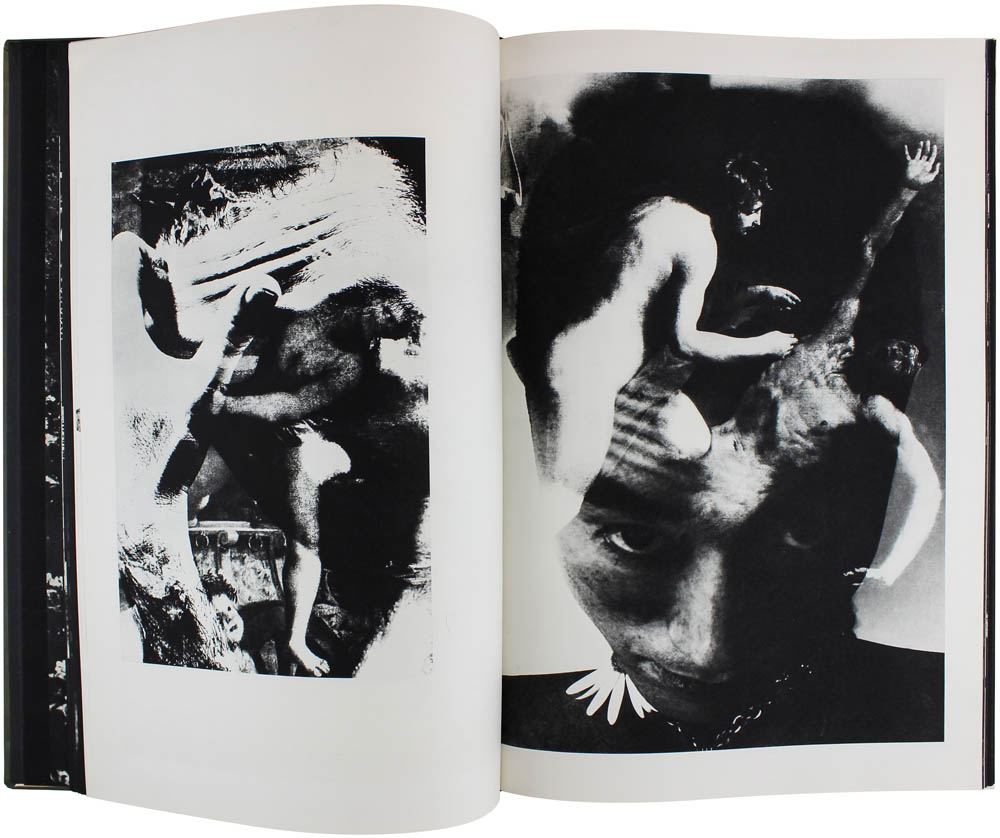

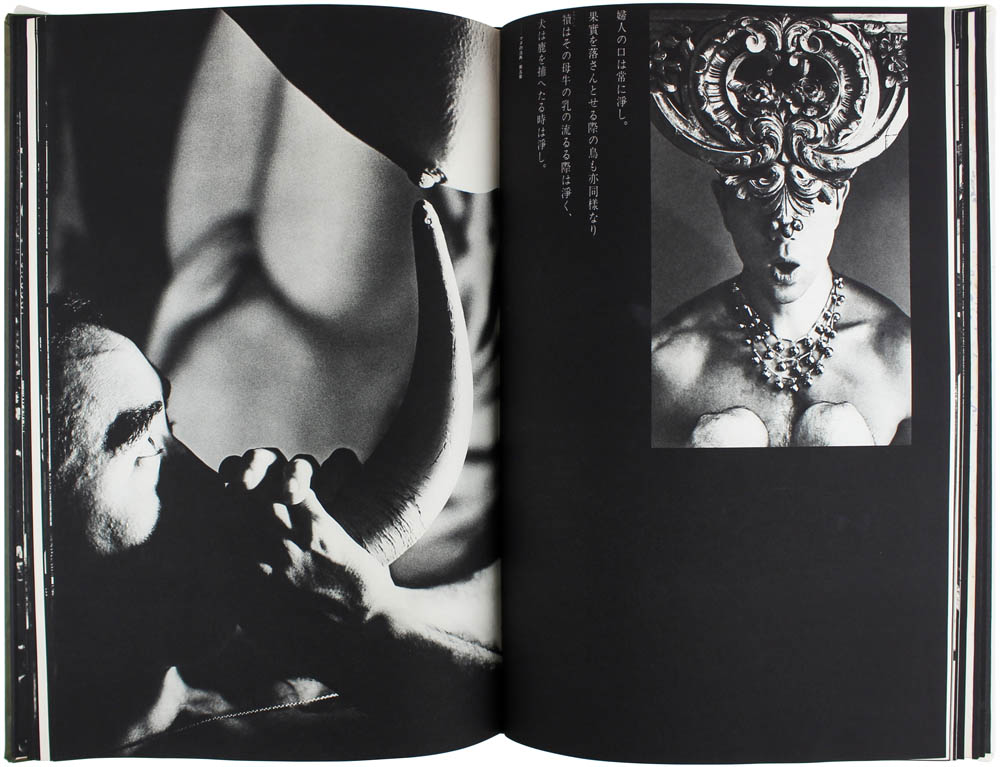

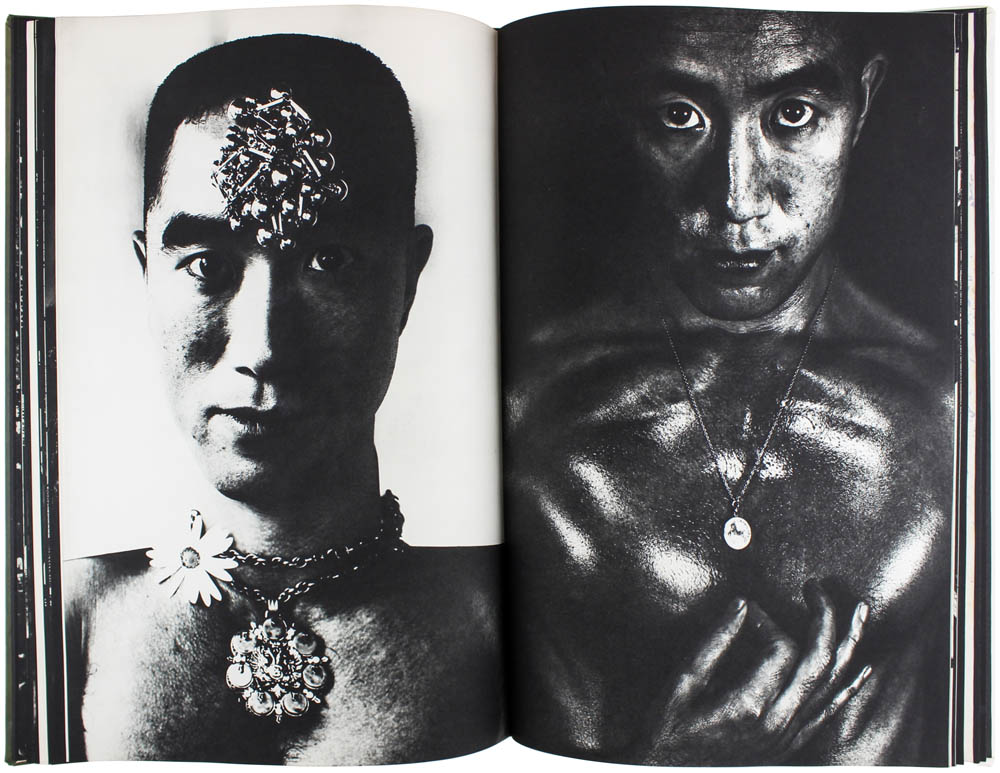

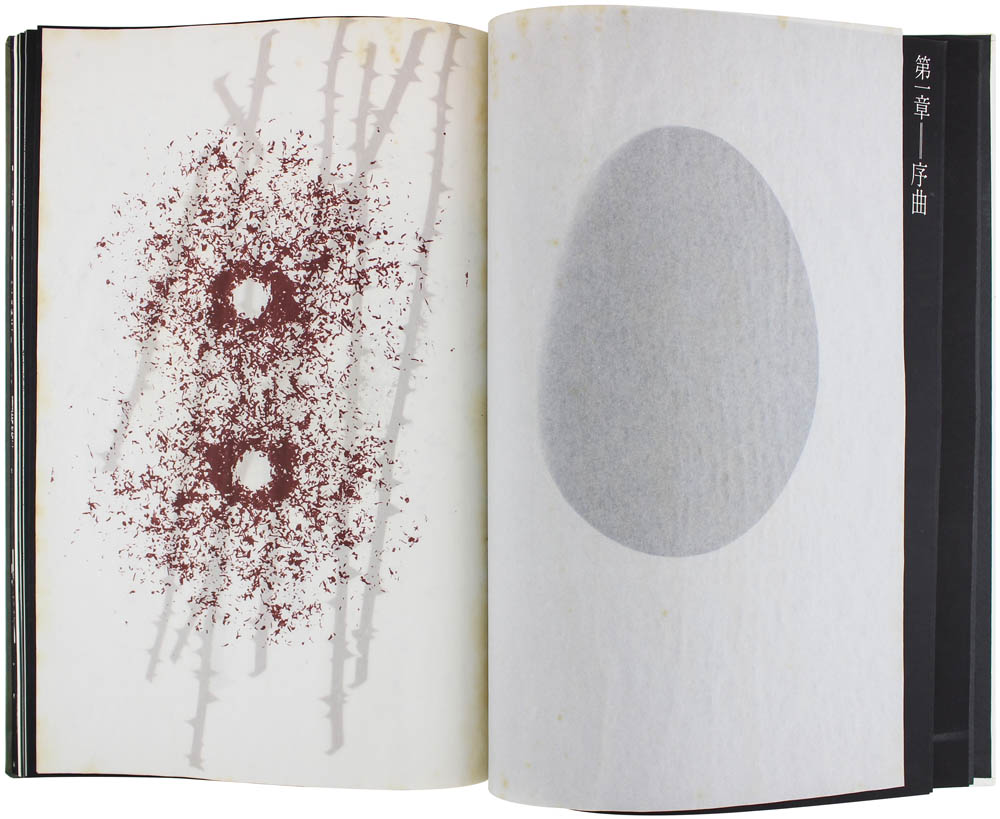

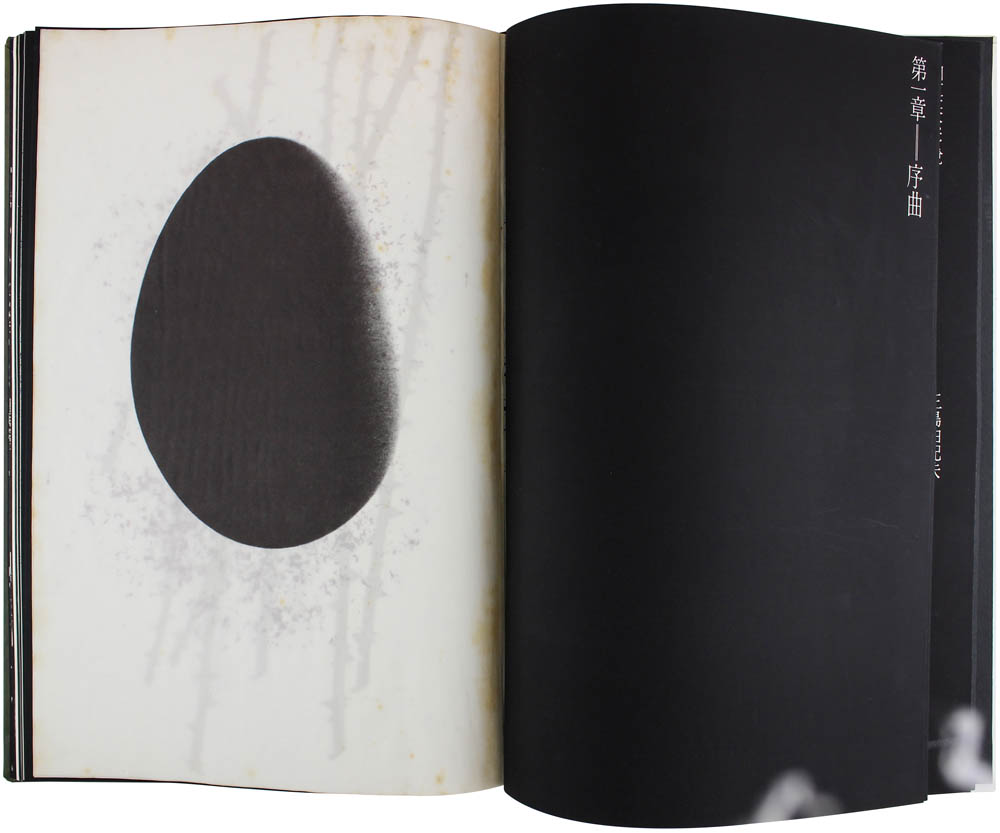

Although it is his series after Barakei , Kamaitachi, in which Hosoe more literally evokes yōkai, Mishima’s characterisation in the Barakei series is at turns as playful and menacing as the yōkai themselves. Like most yōkai, the Kamaitachi have shape-shifting powers, travelling in packs of three, their sharp claws raking through the winds that carry them, but rarely seen. The first yōkai is said to pummel its human victim, the second gauges their flesh, and the third vanishes the wounds, magically healing them visibly, though the lacerations are still there for the sufferer to torment.

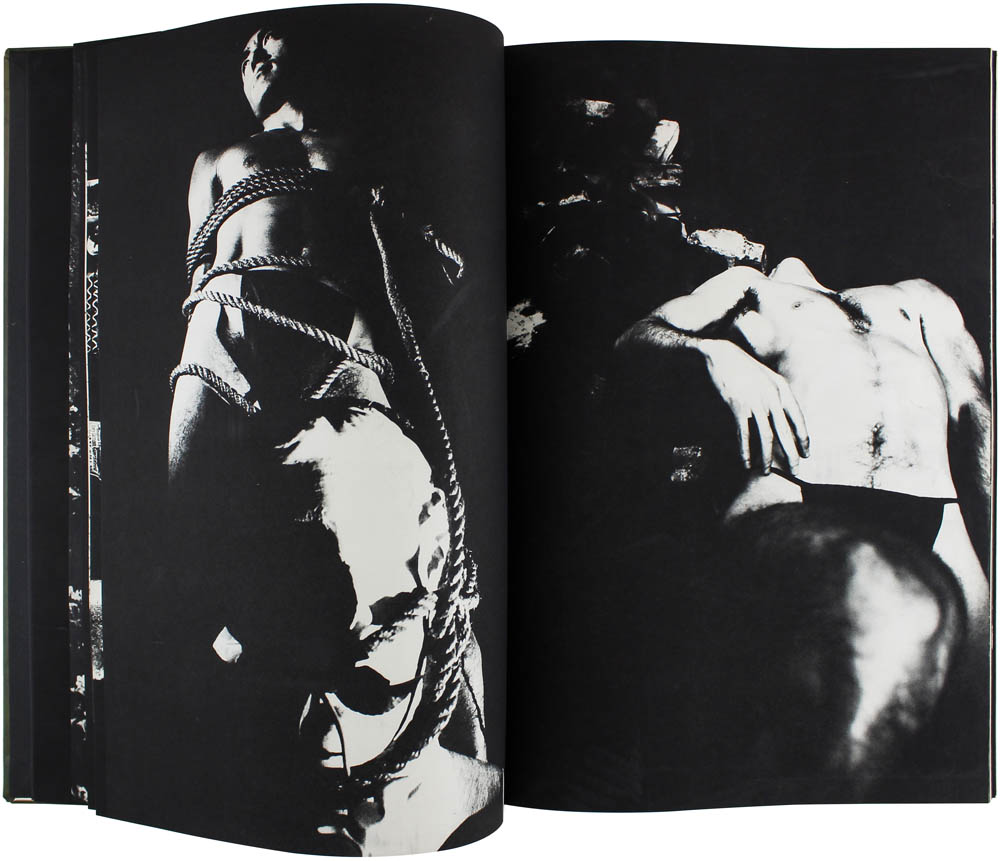

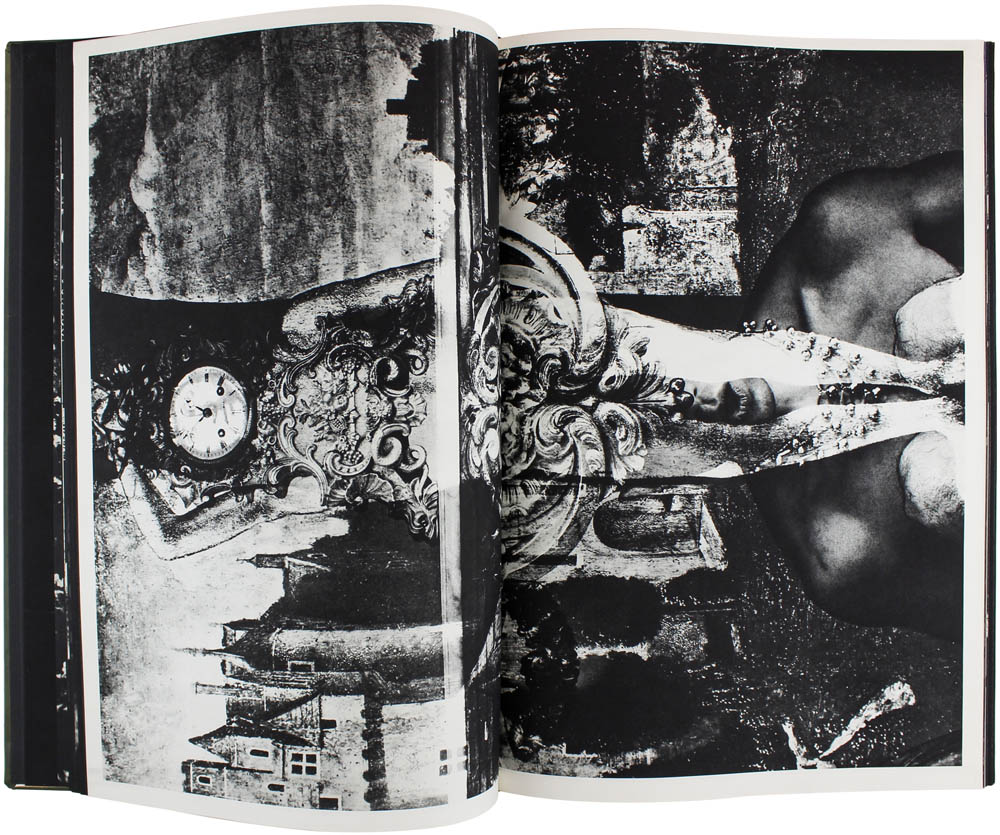

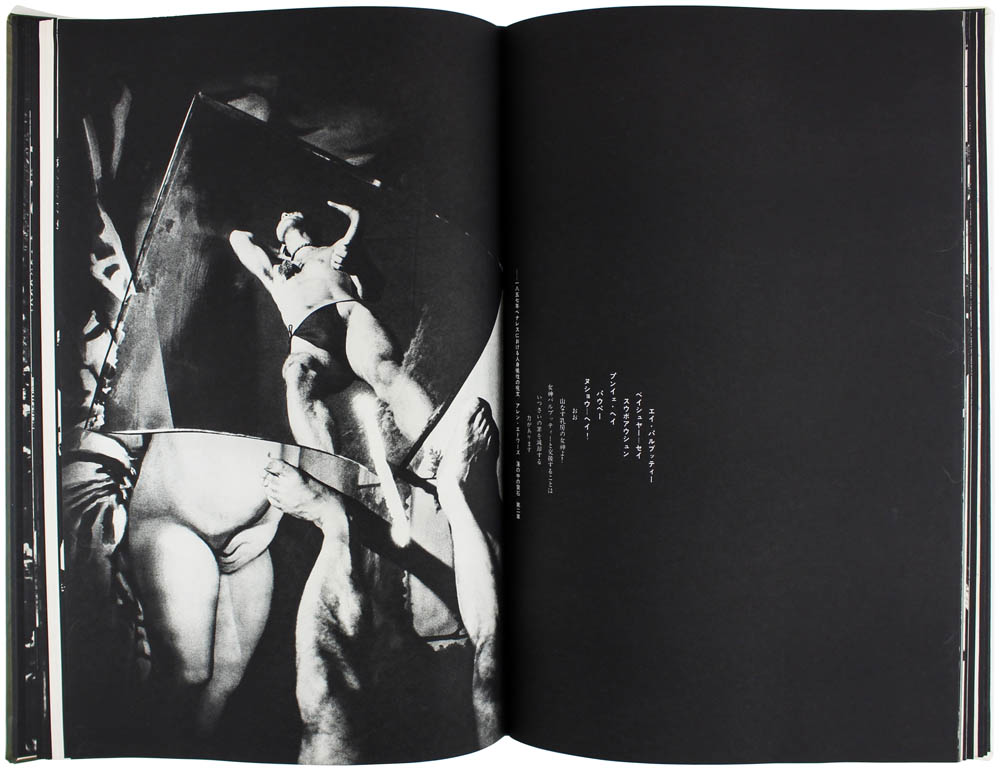

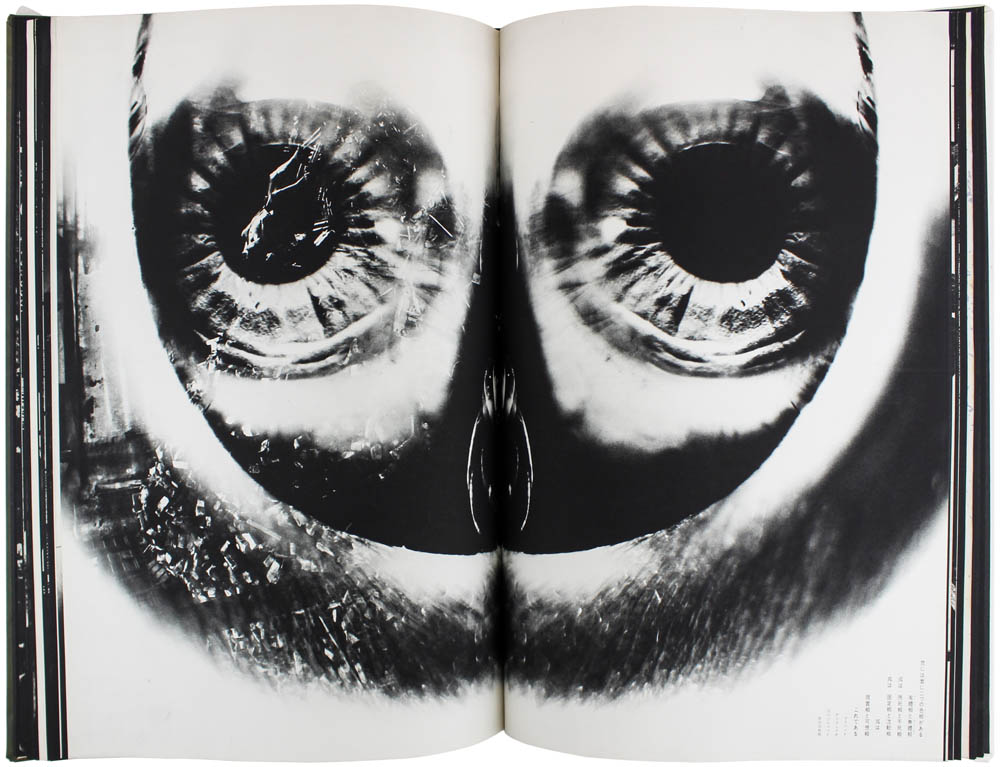

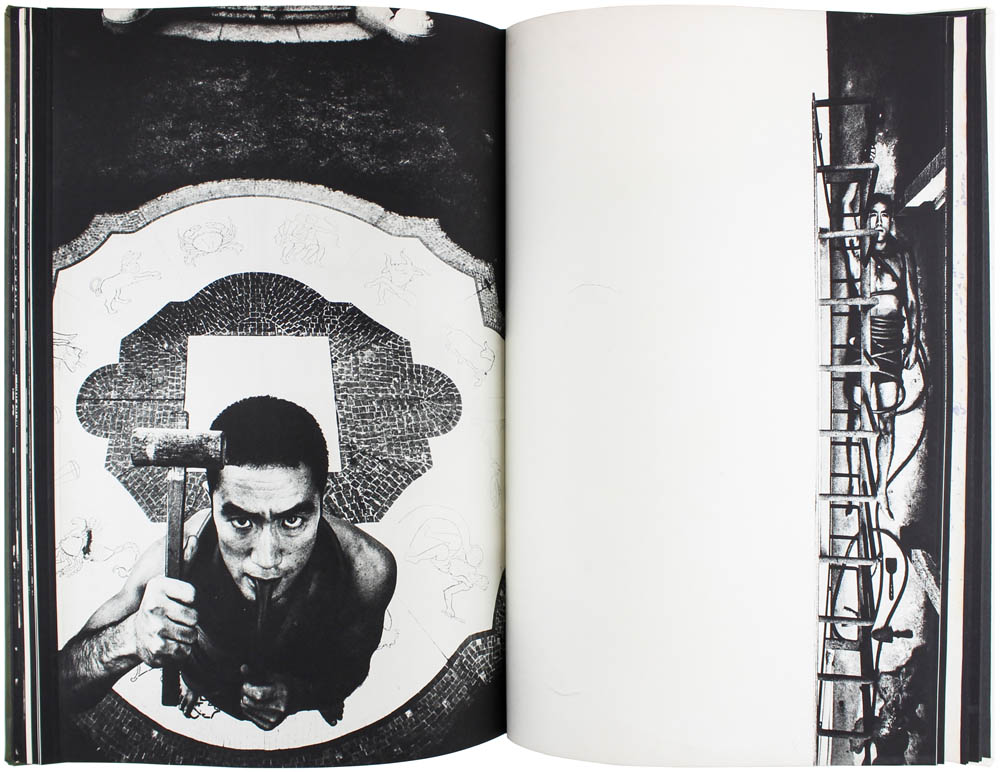

In Barakei, Mishima becomes such mythical creature. Yet he is the one inflicting wounds on himself, his naked body splaying with others, creating forms that don’t seem human. The first photo Hosoe took of Mishima shows him ferociously intent at the lens looking down on him, hammer poised near his head, hose around his neck pulled taught with his mouth, and a mosaic of the western zodiac behind him; a wheel of fortune full of other mythological creatures spurring him on.

As Greg Fallis once wrote, Hosoe’s photography was shaped by “Inexplicable suffering. Wounds inflicted by beings whose motives are beyond comprehension. The human and the supernatural encountering each other, unpredictably but inevitably.” For a photographer who came of age just as Japan became physically, culturally and emotionally denigrated and destroyed after WWII, it made sense that that ‘inexplicable suffering’ and ‘motives beyond comprehension’ would infuse Hosoe’s work.

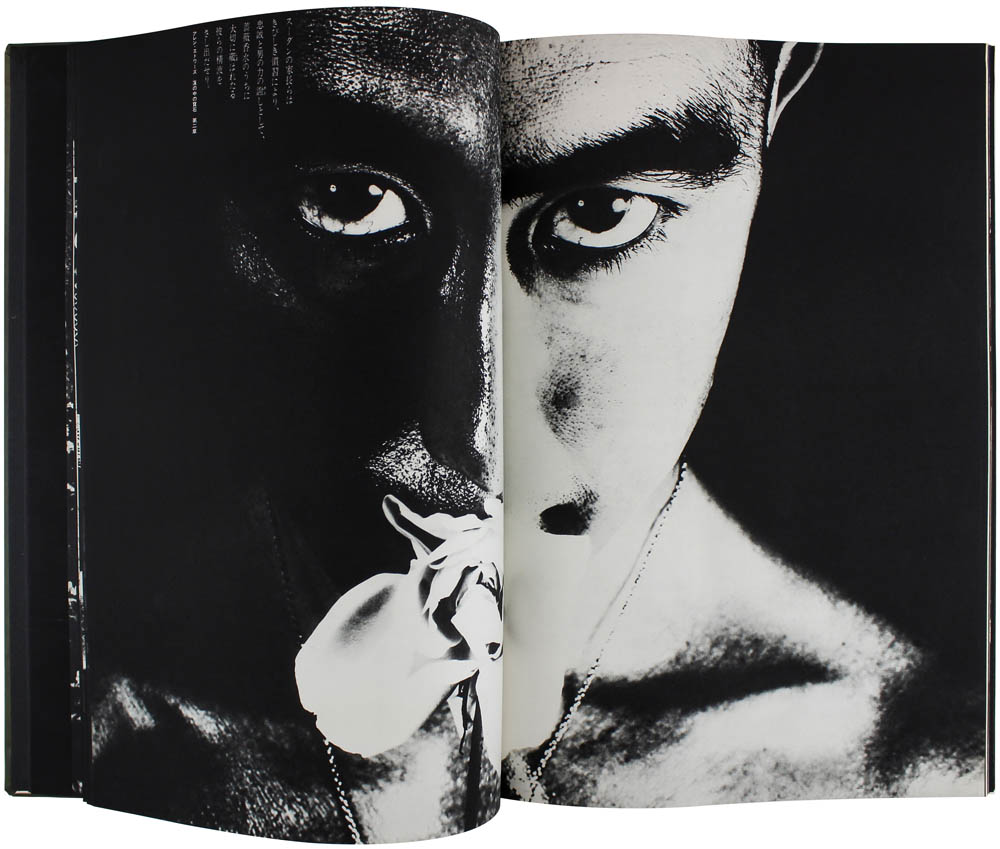

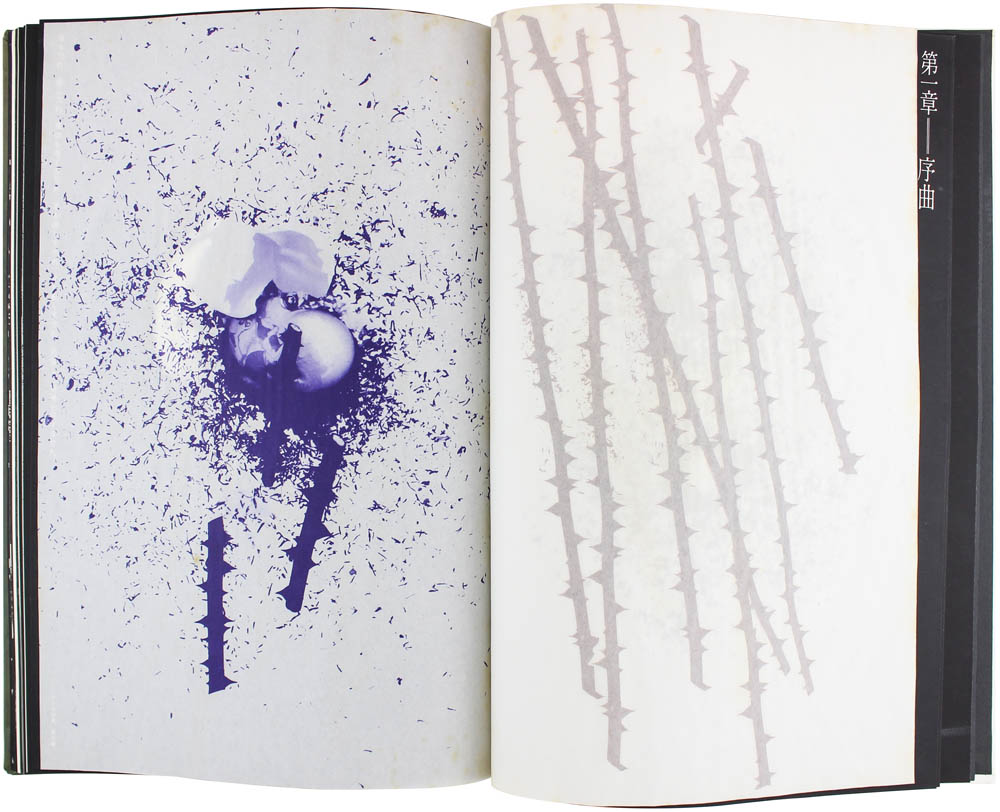

Hosoe himself said of Barakei that “the theme that flows through the entire body of work was ultimately ‘Life and Death’ through Yukio Mishima, borrowing his flesh and using a rose as a visible symbol of beauty and thorns.” And so seven years later, when Mishima used his own flesh to commit seppuku in protest (ritualised disembowelment originally performed by samurai), it was meant as a piercing statement of his to the government, to return power to the Emperor, who in the wake of the World War II had disavowed it as part of the conditions of Japan’s surrender.

In doing so, it rendered Hosoe’s Barakei series to mythic status, as it had Mishima’s life; him choosing the honourable code of the samurai to try to provoke and cement what it means to be Japanese, when the country and its inhabitants were trying to recover it. The rose of ‘life and death’ seen blooming from Mishima’s mouth while he looks defiantly into Hosoe’s camera, as if to say ‘what thorns?’, are wounds as invisible as those the Kamaitachi inflict. In the context of the history that came before and after it, these images cut deep.

Text by Shana Chandra | S/TUDIO

Images courtesy Harper's Books